Pricing is one of the biggest headaches for companies. Unsurprisingly, we can observe radically different approaches among the scientific and economic players.

As a young engineer, I started my career at Amadeus, the European GDS (Global Distribution System) and yield management (or revenue management) specialist. I found out how complex the calculation of airline ticket prices was, a complexity I had hardly experienced as a consumer.

A few years later, here I am at Mercio, the retail pricing specialist. I was pretty confident that I would make good use of my knowledge of yield management for retail pricing. If I think this through, it wasn’t as simple as that. The specifics of retail, and in particular brick and mortar, require us to think about pricing differently. Many publishers adapted yield management to e-commerce (and they were right), but this method quickly presents limits when it comes to pricing in store, for products on the shelf.

The different approaches do not compete with each other, each one corresponds to a business need. Between buying a plane ticket online and buying a drill in a shop, everything differs: price comparability, the frequency of possible repricing, the impact of the price on customer loyalty to the brand/airline, the perishability of the offer… A pricing method may therefore be particularly effective for the first product, but totally irrelevant for the other.

In this article, we look at the origin of both approaches and analyze the relevance of each approach in different business contexts.

A bit of history on these two approaches to pricing

Yield management was first introduced in 1985 in the airline industry by American Airlines. The latter developed and implemented the very first version of this pricing system to respond to the new competition from low-cost airlines, and in particular from the defunct People Express Airlines. The success of this business innovation at American Airlines encouraged its rapid development in the airline industry, but also in the tourism industry more generally (train, hotel, car rental, etc.).

The success of yield management has been accompanied by numerous incremental technical improvements (e.g. improved mathematical models) or more radical improvements such as dynamic pricing.

Retail is based on the purchase of goods in bulk and their subsequent resale in stores. Many goods or services are sold in this way, including food products (205 billion pounds in 2020), DIY products (36 billion pounds in 2020) and many other consumer goods (cosmetics, toys, sports, electronics, etc.).

The retail market is worth almost 421 billion pounds in the UK in 2021, and 70% of sales are made in physical shops. Even though e-commerce has been growing strongly in recent years, the vast majority of retail purchases are made in physical shops. This historical business model therefore remains relevant: consumers go to the shop, look at the shelves, select items in self-service and pay at the checkout.

Pricing in retail has also been the subject of numerous theoretical studies in recent decades and presents mechanisms significantly different from yield management.

Pricing of a physical good vs a tourism service

The nature of the goods or services being sold, as well as the constraints associated with the sale itself, have an impact on how a product is priced.

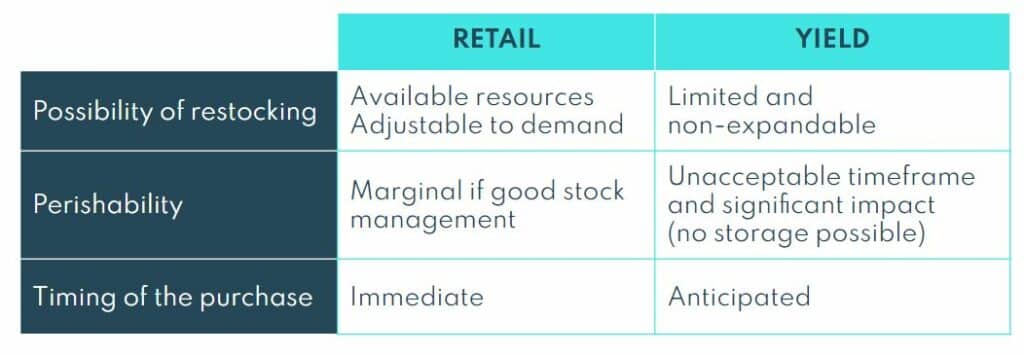

There are three main differences between goods sold in retail in one hand, and in the tourism industry using yield management in the other hand: restocking oppotunities, product’s perishability, and timing of purchase.

Possibility of restocking

By definition, a retailer buys in bulk and then resells the goods in stores. In most cases, the retailer represents a marginal share of the manufacturer’s sales; the product can be considered to be available at will to the retailer – restocking is theoretically always possible.

In practice, it is possible to order additional quantities of a given product; this will have an impact on purchase prices. Under normal circumstances, ordering more volume is beneficial to the buyer and allows prices to be negotiated downwards; but the opposite effect sometimes occurs in the event of a shortage (for example, surgical masks in March/April 2020).

Ensuring good stock availability at the right time in the right place is an important challenge for retailers. As in-store availability is at the heart of the retailer‘s business, retailers have developed logistics to meet this challenge, even in challenging times such as those we have experienced recently. However, money, time and efficient logistics enable retailers to benefit from additional stocks. The challenge is then to ensure a good resale of these products.

In yield management use cases, resources are finite and cannot be easily increased. For example, a hotel has a fixed number of rooms and will only be able to rent, each day, a maximum of that number of rooms. Even assuming that the room rate could be increased significantly for one night, there is no immediate possibility to accommodate more people in this hotel.

The same reasoning also applies in transport (air, rail) with a number of seats available for each journey or in rental with a defined fleet of vehicles.

Perishability

As mentioned above, stock management in retail is crucial to the success of a retailer- and even more difficult during a health crisis.

Not having enough stock brings its own problems (see above), having too much stock is also problematic: products are not sold, occupy valuable shelf or warehouse space and can end up being thrown away or sold at knock-down prices.

Good anticipation and stock turnover limit ‘breakage’ – the term used to describe products purchased at a normal rate but not sold at their usual price – for products at the end of their life.

In the food industry, between 3 and 4% of products are « lost » with these expired products. Several solutions are emerging to limit waste (online destocking sites, donations to associations with fiscal deductions…), boosted in France by the AGEC law of February 2020.

Counter-intuitively, food is not the sector with the highest rate of breakage; sectors subject to fashion phenomena such as clothing (30% unsold) or toys show much higher turnover rates in their inventories in order to continue to offer the trendy products, and therefore a higher proportion of unsold goods as a proportion of turnover.

It should be noted that for non-perishable products (toys, clothing, etc.), the date of removal from the shelves remains at the discretion of the store (launch of the new summer/winter collection, for example). There is therefore no strong deadline, except for the one that the retailer needs to meet in order to remain relevant in terms of offers for its customers.

For tourism services whose prices are determined by yield management, each stock has a redhibitory « expiry » date:

- Seats not sold once the aircraft has taken off are lost forever

- Unoccupied hotel rooms are definitely lost the next day

- Cars not rented before the agency’s closing time will remain in the car park and will not generate any income for that day.

Each unsold item has a cost for the company, of course, and above all represents a missed revenue opportunity. The issue of unsold goods in the yield sector is crucial, as the rate of unsold goods is much higher than in the retail sector. For example, almost 20% of unsold goods in the airline sector (a figure that rose to 40% before COVID, with the health crisis) or between 20% and 50% of unsold goods in the hotel sector (with a strong variation depending on the tourist season; a rate that rose to more than 90% in Europe during the COVID).

Various techniques are used to optimize these fill rates (last minute promotions, overbooking, etc.). And of course, price optimization must take into account this unsold rate as a primary factor in the price calculation.

Timing of the purchase

Another important difference between the two types of goods sold is the time gap between the act of purchase and the taking of possession of the goods.

In retail, the products pass into the possession of the consumer at the moment when he pays at the checkout. For some services, the act of purchase is much earlier than the moment when the consumer obtains the consideration for his expenditure. This anticipation of the act of purchase allows the salesperson to:

- Have historical purchasing data for a given resource

- Segment customers according to when they buy (those who anticipate a lot and those who buy at the last moment)

- Make it acceptable to customize the price according to the time between the purchase and the actual service rendered (and not just « at the customer’s discretion »).

Yield management algorithms can therefore optimize the price of the same resource over its lifetime – from opening to purchase to expiry – afin order to maximize the revenue derived from it.

It should be noted that the timing of the purchase is as important a criterion as the previous two for the application of yield management. A striking example is that of restaurants: this is a service in the tourism sector which meets the two previous criteria – a limited and non-expandable number of tables and an expiration of unfilled tables at the finding of a service. However, the timing of the purchase makes it impossible to apply yield management in this sector.

This difference in the nature of goods sold in retail and yield – available resources, expiry and timing of purchase – leads to differences in price calculation.

Before analyzing this difference in pricing philosophy, let us review other important differences concerning the impact of competition, price consistency and enfin operational constraints.

The weight of competition

In a market where the consumer has different alternatives and is free to buy from the brand he or she prefers, competition (or the lack of it) has an impact on price.

However, while prices in retail cannot be considered without taking competition into account, yield places less emphasis on competition and is generally a second order factor on price.

This difference in the consideration of competition is due to 3 main characteristics of the wider market: product comparability, consumer price knowledge and customer fidelity.

Comparability of products

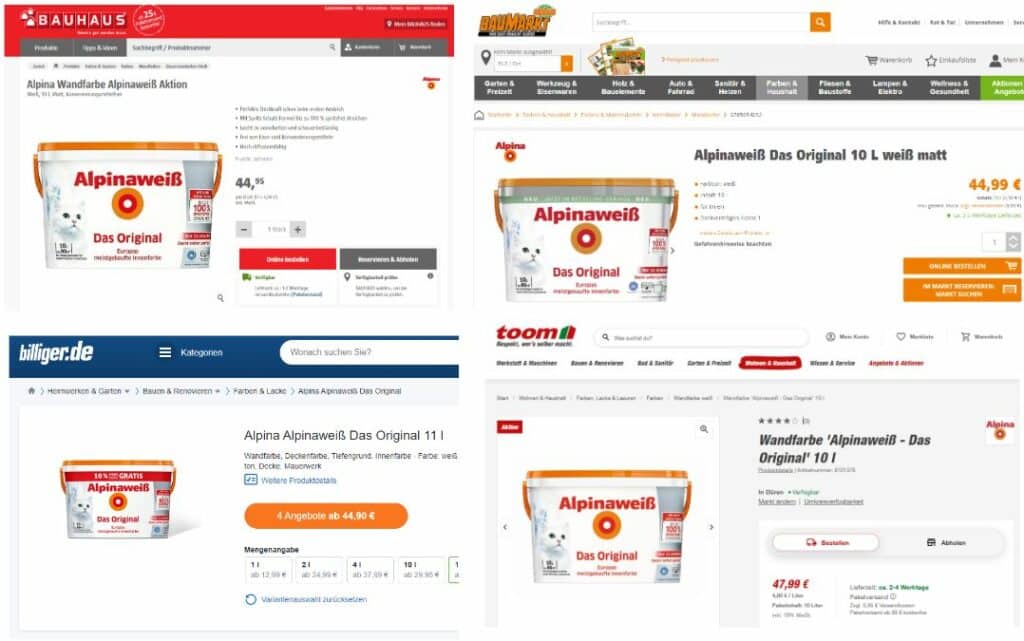

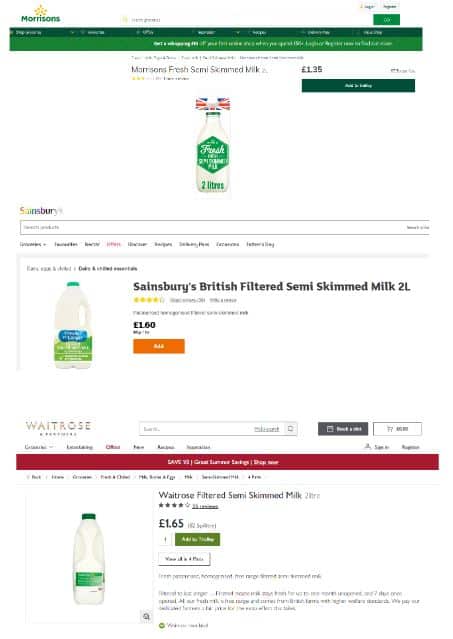

By definition, in the retail trade, products sold by a retailer – and bought wholesale from a manufacturer – are also sold by other competitors in the market.

This possibility of finding exactly the same product for the consumer in another shop allows the consumer to compare prices.

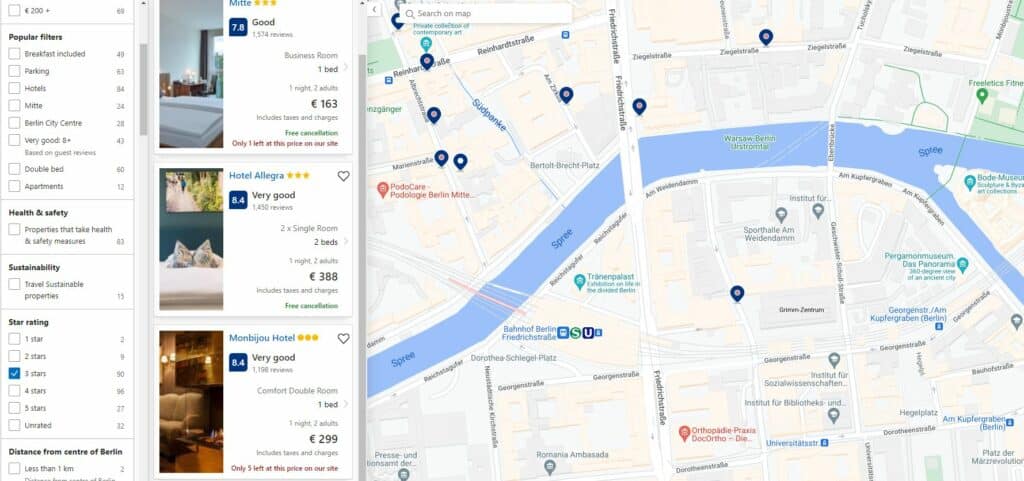

This is more difficult in the yield sectors, where there are many ways for the customer to access and compare different offers, but each service is unique. A single plane may take off/land at a given time from a given airport, another hotel will necessarily be different in terms of service, location, etc.

Many retailers develop a unique assortment under their own brand name, known as a private label. The exact product is therefore only available in one store and not in its competitors. However, similar products from competitors often exist and meet the same customer need; the consumer still has the opportunity to compare prices.

Knowledge of prices by buyers

Everyone has a good knowledge of the prices of the products they frequently buy.

The frequency of food purchases makes this sector distinctive; the customer visits the shop regularly and discovers the prices at that time. There is therefore a strong challenge for food retailers to attract new customers to the shops and promotions are used to this end. Once in the shop, the customer buys the products they need – going to another store without buying anything would be time-consuming – and they will get an idea of how expensive the store is based on the prices they know elsewhere and the overall price of their basket.

In other retail sectors, price discovery also takes place in shops and of course on the internet. Depending on the consumer and the type of goods he or she is looking for, the prices of different brands are compared differently:

- Each customer has a different sensitivity to price; a student will shop around more than a member of a high-income household

- The type of product purchased, and in particular its price, will have an influence on the comparison effort between retailers.

The more expensive a product is, the more time the customer will spend comparing its price; for example, a kitchen will be the subject of several hours of research, but a set of 4 plates may be bought without comparison if the price seems right at first sight.

This price comparison process is more or less long and laborious. It represents an effort for the consumer who will therefore decide whether or not to make this effort depending on the products being considered for purchase.

For the products covered by the yield, the frequency of purchase is generally low (with the exception of certain types of customers such as professionals). In addition, the high variability of the price of the same product over time (6 months before departure vs. the day before) blurs the customer’s final knowledge of prices.

The customer therefore generally has only a very imprecise idea of the price. What is the price of a Koln – Paris train journey bought today for 2 months from now?

This difficulty in comparing prices in this sector has also given rise to a new intermediary in the value chain: price comparison services. These new players now occupy an important place, as 72% of French people use a comparator to book a plane ticket.

Customer loyalty

The acquisition of any new customer has a cost. In retail, this cost includes, for example, advertising campaigns to publicize the brand and the various mechanisms for convincing a potential customer to give up his habits and come to a shop that has not yet been visited (discount coupons, events, etc.).

Thus, customer loyalty is a major issue in order not to waste the investments made in customer acquisition. Retailers implement various mechanisms to develop fidelity (for example, loyalty cards) but one of the primary factors of fidelity – or on the contrary of infidelity – is price.

What does it mean to be competitive for a company that sells tens of thousands of different products in hundreds of shops? This is a complex subject that deserves an article of its own, and we’ll get to it soon!

But one thing is for sure, lower prices than competitors on certain visible products will ruin customer acquisition efforts…

This is not the case in yield! The customer is not always aware of the value of the service they are buying; this is the case when the booking is made through a travel agency, or even when the customer books via an online comparator, but does not go down the list.

And even if a seller’s price is heavily discounted relative to competitors at the time of purchase, the seller will not have the reputation of an « expensive » seller and will be reconsidered for future purchases.

Customer loyalty remains important in yield, but it will be developed as a priority on factors other than price: frequent flyer programmes, premium service, …

Yield can define the price of a product in isolation from the competition. Conversely, pricing in the retail sector must take into account the competition when calculating the price to ensure a good price image and consolidate the loyalty of its customers; products have a value known by the consumer. This value allows the customer to judge whether the price of a product is depositioned in that store or not.

Of course, the effect of competition is not excluded from the yield, but it is used as a second-order factor in the price calculation. For example, mathematical models can take into account the effect of competition in the price response. Or else, on a small part of the company’s sales, such as on entry prices or promotions.

It should be noted that the consideration of competing prices in retail does not necessarily mean systematic competitive alignment and therefore a price war between retailers. Other factors such as product quality or even the in-store experience (cleanliness, advice, etc.) can be differentiating factors and therefore a price positioning that is not necessarily aligned with competitors, but with a coherent price differential. In retail, each market, each brand, each product category, will have a differentiated pricing strategy that adapts to consumer expectations.

Consistency of prices in the same catalogue

Just as a good that is difficult to compare with competing goods can define its price independently of the competition, the degree of comparability also has an impact on the extent of price consistency within the seller’s own offer.

An extensive catalogue allows you to capture a larger share of the market by meeting a wider range of needs, regardless of the service or goods sold.

However, whereas the offer in yield is well segmented – and therefore the customer has few points of comparison – retail offers several products to meet the same need and therefore the opportunity for a customer to choose one product over another.

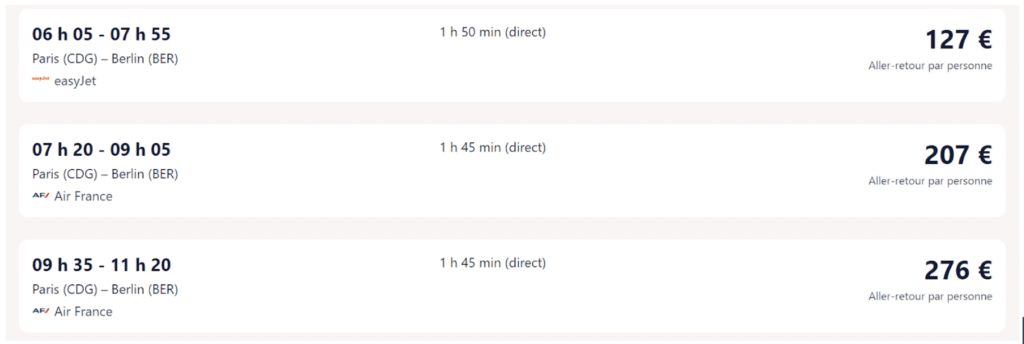

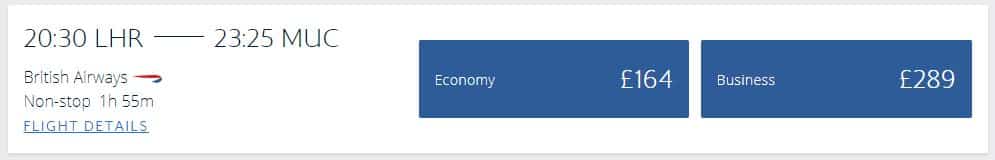

To illustrate this difference, let us first take the example of a plane ticket between London and Munich.

The same airline offers other destinations, but the need is usually well defined in terms of destination – in this case Munich – the customer does not consider these alternatives.

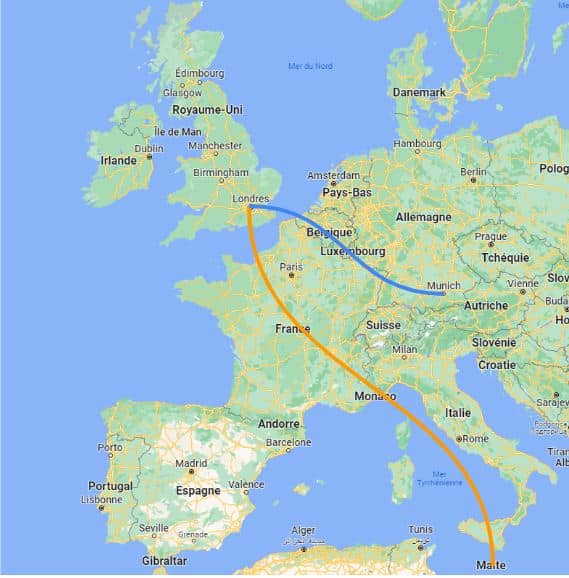

Therefore, the customer will not compare the ticket between London and Malta of the same airline, same date, almost same time, and same class.

The map below shows these two flights:

In this example, there is a ratio of 1 to 2.5 between price and flight distance/time between these two alternatives. This difference is possible because the customer will not compare these two alternatives when making a purchase. Nor will they necessarily compare business class and economy, or tickets for later dates if they need to travel in that period.

This segmentation of the catalogue is a challenge in order to identify the different types of customers, determine the prices they are willing to pay and then to price these products independently of each other.

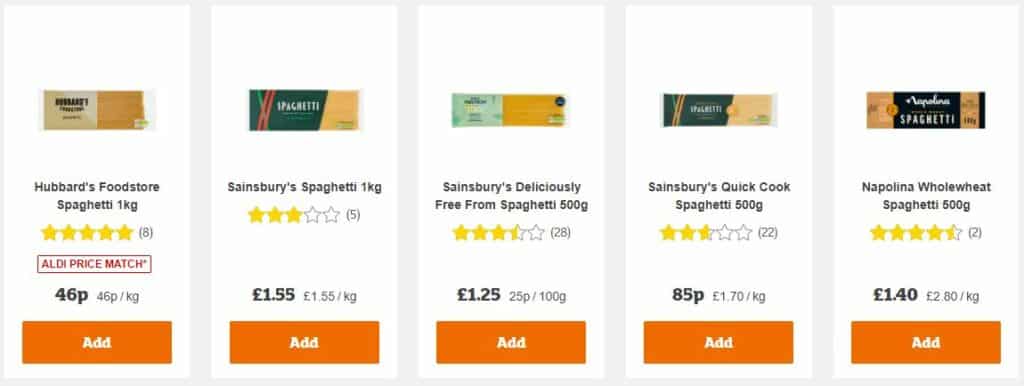

In a shop, or on an e-commerce site, the consumer has several products in front of him that meet the same need. The comparison will be made between products in the same department. The consumer’s trust will be based on the consistency between the differences in price and the differences in perceived value, and the consumer will choose the product that seems to be at the best price in relation to the perceived value.

pasta ».

Even for a very specific need, the consumer will usually be able to choose between different brands, qualities, volumes… The customer’s habits may direct him to a product by reflexe, but a lower price difference or a more important product may switch to a more premium or lower quality product respectively.

In order to ensure a good flow of the various products on offer and to direct customers towards the highest margin products, retailers must price products that meet the same need in a coherent manner, i.e. in relation to each other. This is an additional difficulty in retail pricing that we do not find in yield management.

Operational constraints in the application of the price

In addition, a price must be operationally applicable. There are two important operational differences between yield management and pricing in retail: acceptance of personalized prices by customers and price updating.

Price customisation

The advanced customer segmentation of yield allows a different price to be offered for each final customer. This method of tarification – the famous “each passenger on the same plane paid a different price” – is acceptable to customers.

The high degree of segmentation of supply in this sector has been a determining factor in making this apparent “unfairness” in prices acceptable. It is understandable for the customer that a train ticket booked well in advance is cheaper than the same ticket booked the day before departure. The historical sales channels without a displayed price – travel agencies – have participated in the implementation of this price customisation. This acceptance of price customisation has enabled the new sales channels, via the web in particular, to follow suit and offer a unique price to each visitor.

This personalisation of prices is not possible in physical shops where the price must be legally displayed. Theoretically, prices could be individualized in e-commerce. The limit here is not technological, but psychological; this personalisation of prices in retail is felt as unfair – an impression on the part of the consumer that the price is « at the customer’s expense » – and is the subject of a frank and virulent rejection by the market.

Even the formidable Amazon machine ran into trouble on that topic and had to back down with apologies for its customers (link)

Price updates

In addition to the customer acceptance criterion, there is the operational updating of prices. It is relatively « easy » to update prices in e-commerce, as this process remains digital. Updating paper labels adds significant operational constraints and additional cost.

Electronic labels, which are on the increase, are facilitating this updating of prices on the shelves, but paper labels still represent a significant part of the market and the cost of updating the price must be considered at each price change. Price management for paper labels is one of the most recurrent questions asked to Mercio by retailers, as few of them are fully equipped with electronic labels today.

In addition to these technical constraints, there is a legal constraint which prohibits the presentation of a price at the checkout that is higher than the price on the shelf.

A customer shopping in the shop will be surprised to be presented with a different price at the checkout than the one they saw on the shelf. E-commerce is aware of this problem and sites need to inform the visitor when the price of an item in the shopping cart changes between the time it is placed in the cart and the final purchase.

Conclusion

Yield management and pricing in retail are two methods of calculating prices that fulfill different objectives and are adapted to different contexts.

Where yield management will optimize the revenue derived from a fixed resource, limited in time and which can be considered a priori independently of other alternatives on the market – whether from competitors or from the same vendor’s offer – pricing in retail will seek a good balance between turnover, margin and customer loyalty.

The multiplicity of constraints – between products in the same catalogue, with competing catalogues or imposed by the retailer’s strategy – combined with the size of the catalogues (several tens or even hundreds of thousands of references) and the number of points of sale are some of the difficulties that retailers report to us concerning price management in retail.

And the challenge we face every day at Mercio, is to enable retailers to position millions of prices that encourage consumer buy-in in shops.